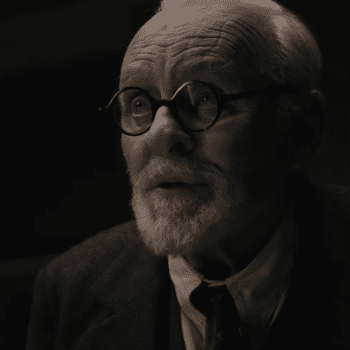

Hercule Poirot is a man of exactitude. He loves his mustache’s perfect symmetry. He likes his breakfast eggs to be exactly the same size. He understands the world is far from perfect, but he believes that, somehow, it wants to be.

Murder is a blemish on that sense of divine order, the detective insists. “I believe it takes a fracture of the soul to murder another human being,” he says. He admits that the world’s chaos, and his own preference for order, can make life often “unbearable,” but it allows him to detect wrongdoing easier than most. And it gives him a certain clarity of purpose that comes in handy when solving crimes.

“Whatever people say, there is right, there is wrong,” he tells us. “And there is nothing in between.”

But when Edward Ratchett, a one-time gangster (played by Depp) is murdered, Poirot’s sense of right and wrong is challenged. We learn that Ratchett literally got away with murder himself.

As such, the movie paints his death less as a murder and more as an execution—one that comes with, perhaps, divine blessing.

Poirot may believe that murder takes a “fracture of the soul,” but others on the train might classify this particular murder as a clarity of purpose. Let’s face it: None of the suspects was exactly broken up about Ratchett’s death. That’s why they’re suspects. He got what he deserved, they might say. Ratchett himself tells Poirot that, if there is an afterlife, “I will face judgment.”

We see this sense of divine judgment most clearly in missionary Pilar Estravados (Penélope Cruz). Pilar says that “Sin does not agree with me,” and she tells Poirot that she’d never murder anyone. But when it comes to Ratchett, she grows more enigmatic. “Some things are in God’s hands,” she says, and then seems to compare Ratchett to the Prince of Darkness himself. “Like Lucifer, he must fall,” she says.

Which makes the optics of the climactic scene all the more significant: The suspects are arranged to reflect Leonardo da Vinci’s The Last Supper, with a critical character sitting in Jesus’ chair. The movie seems to suggest that Ratchett’s death wasn’t murder, but rather a triumph of goodness over sin and evil—a wrong finally righted.

Poirot wavers in his convictions: If a murder is just, is it really murder?