“When do you get your soul?”

An agnostic friend of mine asked me that in college: Not what or how or why or even if, but when—a question that neatly asks all the other questions too, hinting at the incredible intricacies and, perhaps, paradoxes, that come with the concept of an immortal soul. I’ve thought about that question often since. Sometimes I think about it when I consider abortion or artificial intelligence or even when I see a gorilla in a zoo.

When do you get your soul?

And I thought about it while watching Blade Runner 2049.

I’m not going to say much about the movie right now, in part because I’ve been asked not to and, in part, because if you want to see it, you really should see it spoiler free. I don’t think that this blog gives much away.

But it’s fair to say that this Blade Runner, like the original 1982 movie, is concerned with some interlocking, and inherently spiritual, questions: What does it mean to be human? What makes humanity special? Who has a soul? When do we get it?

It’s a question that K (Ryan Gosling) asks himself during this evocative, powerful but overly long movie. (It’s also a pretty hard R when it comes to sex and violence.) It’s a question inherent to his gig as a blade runner—someone who hunts down and “retires” replicants who look, sound and even feel the same emotions that we do. They’re about as close to “human” as you can get: By 2049, replicants have even been graced with implanted memories. These things eat. They breathe. They cry. They bleed.

But do they live? And is it human life? Sometimes we can almost hear the replicants in this movie ask themselves the same questions. Like Pinocchio, they wonder when they’ll be “a real boy.”

But to be that “real boy”—to be truly human—society tells them they need something else, something they don’t have and perhaps can never get: A soul.

In a sense, the Blade Runner movies work only when we buy into the notion that we have a soul—that there’s something special about us, about humanity. If there is no such thing—if we lack that divine, immortal spark inside us—than we really are simply shambling heaps of organic matter, animated by luck and inherently little different from the animals we eat or (in the movie) the replicants we make.

But society in Blade Runner 2049 assumes that we do have a soul. Human life may be cheap at times, but it’s still special. In contrast, replicant “life” is, by this bleak society’s standards, not life at all. Replicants are manmade constructs, sophisticated machines to be extinguished at will, to be snuffed out on a whim. They have as much inherent value as a well-crafted puppet.

But the movie forces us to question that division constantly—even as its characters question it, too. Even the most confident and clueless unwittingly blur the lines.

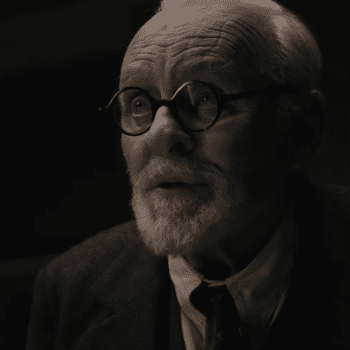

Take Niander Wallace (Jared Leto), the movie’s replicant industrialist. He is, perhaps, the character exhibiting the least conflict over the nature of replicants. He makes them, after all: As such, he sees himself as a god-like being, and the movie paints him a bit like Jesus. He dresses in white, he sports a beard, and his “office,” as it were, consists of platforms set atop rippling water—making it look, at times, as if he was walking on it.

(Interesting, too, that Wallace is blind: In some schools of gnostic thought, the lower-case creator-god—the Demiurge—is blind in some ways, as well, molding the material universe while being wholly unaware of the spiritual world and, especially, of the greater, all-powerful, upper-case God. The demiurge is sometimes called Samael, or “the blind god.”)

He calls his replicants “angels”—an interesting choice of words, given that some theologians believe that angels lack souls. At other times, he calls them his “children.” The very word connotes that the replicants are, in some way, precious to him. And yet, he doesn’t hesitate to destroy his children: We see him “retire” one practically as soon as it exits her artificial womb, slicing open her belly and letting her bleed to death on the floor.

K “retires” his share of replicants, too. It’s his job. And when he does so, he plucks the right eyeball from the head to take back to headquarters. The eyeball bears the replicants’ serial number, and serve as confirmation that the job was done. But given Wallace’s blindness, the use of an eyeball here is pretty interesting. It’s almost as if it wasn’t enough to kill the replicants, but blind them, even after death, as well. If the eyes are the window to the soul, it makes sense to separate and package an eye to both dehumanize and, in a way, de-spiritualize the subject. Those who run are symbolically blinded, as if to confirm they’re only pale facsimiles made by a blind creator.

But could these replicants be more than machines designed by man? Could they be part of God’s design, as well?

I’m reminded that, throughout Scripture, we’re told repeatedly that without Christ and God’s love, we are dead. We walk and breathe and eat and bleed, yes. We look as though we live, much like replicants. And yet, the Bible says that something special happens when we turn our lives over to God. We’re suddenly animated in a whole new way. We’re given a new reason to live and to love. Maybe we’re more willing to sacrifice for others, just as Jesus did for us.

“Greater love has no one than this,” we read in John 15:13, “to lay down one’s life for one’s friends.”

Late in the movie, one replicant seems to, in a way, echo those sentiments to another. “Dying for the right cause is the most human thing we can do.”

In Disney’s Pinocchio, the titular character becomes a real boy when he shows love and selflessness and a willingness to lay down his life for his “father” in the belly of a whale.

We see something that echoes Pinocchio in Blade Runner 2049. Without saying too much, a replicant makes a sacrifice for someone else—someone who might be construed even as a father.

When do you get your soul? This movie asks the question and, like its predecessor, leaves the answer open. But me, I’d like to think that the replicant in question got its soul in that moment of sacrifice. That in that moment, it became a real boy.