When I was covering religion, a Catholic priest drew my attention to something I had never noticed before. While both Protestant and Catholic sanctuaries use a cross as a focal point, there’s often a critical difference. In Protestant churches, the cross is just that: a cross. There’s no one hanging on it, no one bleeding from it, no reminder of suffering other than the symbol of the cross itself. In Catholic churches, Jesus is usually right there—nails, crown of thorns, the whole bit. Protestants, the priest told me, focus on that empty cross, that empty grave, the miracle of His Resurrection. Catholics place more emphasis on Christ’s suffering. It’s that suffering that did the heavy work of salvation for us; his pain, blood and death mysteriously allowed us a new sort of life.

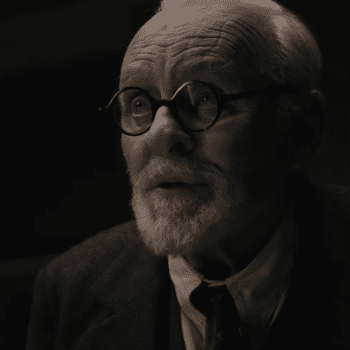

Jesus’ willingness to suffer and die for us is critical in Catholicism. Every Catholic church, cathedral and monastery I’ve ever been in has included a series of paintings, sculptures or stained glass windows depicting the Stations of the Cross—a ritualistic depiction of Jesus’ condemnation, crucifixion and burial. Gibson is a devout Catholic, and his 2004 movie The Passion of the Christ was, at its core, a cinematic depiction of those Stations. It seems like all Gibson’s movies foist his heroes into critical moments of horrific, almost obscene suffering. In 1995’s Braveheart, which won an Oscar for Best Picture and earned Gibson one for Best Director, Scottish rebel William Wallace is disemboweled, shouting “freedom!” as he expires. His Apocalypto hero Jaguar Paw suffers terribly while trying to save his family. Both suffer for others. William Wallace is, unquestionably, a Christ-like figure.

Hacksaw Ridge’s Desmond Doss gets off comparatively easy. But he too is in the midst of incredible suffering. I think that Gibson meant the battle of Okinawa to feel almost biblically hellish—a Dante-like landscape of fire and torment and anguish. Maybe, in Gibson’s mind, Desmond is yet another Christ figure: Instead of suffering and dying for us, Desmond’s trip to Okinawa is meant to remind us of Jesus’ descent into hell, a la The Apostles’ Creed (and 1 Peter 3:19-20)—another element of Christianity that Catholics pay far more attention to than Protestants. Desmond willingly enters into a place filled with the damned, pulling one after another from Okinawa’s hellish pits.

Some have suggested that Gibson’s fascination with blood is a sign of psychosis. But I think there’s more at work here than just a salacious love of gore. The blood is part of Gibson’s religious expression—including in Hacksaw Ridge.

“With the world so set on tearin’ itself apart,” Desmond says, “don’t seem like a bad thing to me to try to put a little bit of it back together.”

Gibson feels like he needs to show that world being torn apart, blood oozing from every rip. It’s only through that sense of horror that Gibson’s heroes can really show the power of their courage, sacrifice and, often their faith—the lengths they’re willing to go to help put the world back together.