The definitive scene in That Dragon, Cancer, is its most frustrating.

I’m in a hospital room. My “son,” Joel, is crying. And the objective … what is the objective? To make him stop crying? To make him feel better? To wait for the doctor?

In most video games, we know what we’re supposed to be doing. We’ve gotta kill Alduin or stop the Joker or take the checkered flag. But there’s no fold-out menu to tell me what to do, no map to show me where to go. And Joel is crying.

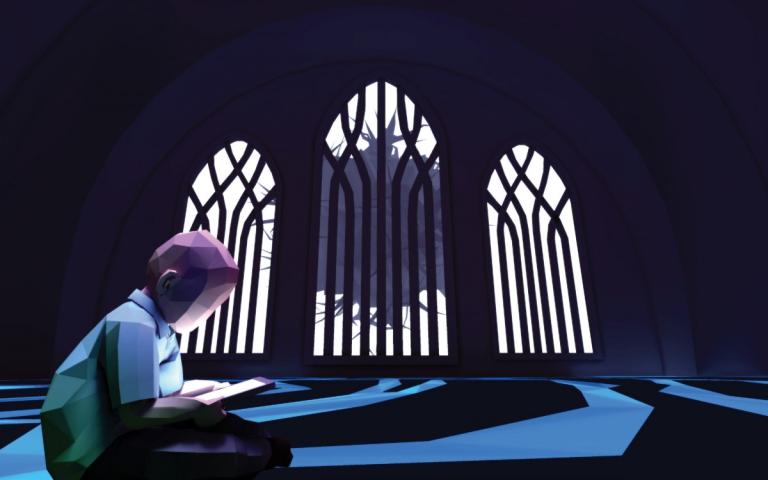

The room is dark, the multi-color of a half-healed bruise. My character, Ryan, talks about why the hospital picked these colors—the muted blues and greens and “purple stripes to hide the stains.” I make him walk to the window, and the camera takes me outside—looking in at Ryan through the window set in a rocky cliff, rain pounding down.

Joel is crying. I’m inside Ryan again. Walking to the crib. To the wall. Going to the bathroom to see if some solution, some escape, might be there. An old-fashioned arcade game stands in a puddle in the bathroom—but none of the buttons work. It sputters and buzzes at me when I try.

Joel is crying. I wander through the room again and again, looking for something I missed, some way out. I click on the door to escape this room. But there is no escape. That’s the point: You’re here. You’re helpless. You and Joel are at the mercy of a disease—of a world—that gives no help and offers no hints.

This is not a game. You play games. They’re supposed to be fun. That Dragon, Cancer is challenging, frustrating and, at times, heartbreakingly beautiful. But it is not fun.

That Dragon, Cancer was designed by Ryan and Amy Green (along with Josh Larson) as a way to process their own very real experiences with Joel, their son who was diagnosed with terminal cancer when he was just a year old. It pulls us into them, allowing us to touch their hopes and fears and, at times, overwhelming fatigue. It’s alarmingly honest and, at its core, buoyantly hopeful. Because while That Dragon, Cancer is, of course, about cancer, it’s also about faith.

The Greens are committed Christians, and their faith permeates the entire game. Amy hopes and prays and even expects a miraculous recovery, but regardless of her outcome, her hope in God never wavers. “We pressed into God, we pressed into faith, we fought until we found peace,” One of Amy’s diary entries reads in the game. “We stood in peace when our flesh wanted to strive more. We stood in peace when it started to feel like laziness or foolishness or both.” She’s often in a boat, cradling Joel as she bobs along the water.

But Ryan struggles. Sometimes he’s depicted underwater, surrounded by pulsing blobs of blackness—cancer, perhaps, or despair. “I’m pleading for God to spare his life, and I’m tempted to despair because self-inspection leads me to conclude I shouldn’t expect much of anything,” he tells us. “And yet my wife is expecting a surprise party from the Lord, replete with presents, supernatural miracles.”

“I envy her,” he says with a sigh.

Many people wonder how it’s possible to hold to faith—to believe in a loving, caring, all-powerful God—in the midst of life’s unfair horrors. That Dragon, Cancer, depicts perhaps one of the cruelest such horrors we can imagine. But in the midst of such horrors, is there anything else to hold onto? That’s all that’s left to us. Faith.

The Green’s story, faith and all, has resonated powerfully with people. “Christian” entertainment often lags behind its peers. But That Dragon, Cancer is breaking ground, and gaming critics—many of them quite secular—have praised this deeply personal story, faith and all. For those who sometimes see “Christians” as judgmental prudes, homophobic conservatives or any of the other myriad stereotypes we’ve accumulated, the simple story of Ryan and Amy Green may force some to see these two Christians as something more: As people.

“The Greens’ religious beliefs are not just alluded to, but placed front and centre,” writes Tom Hoggins in his five-star review of the game for London’s Telegraph. “Amy’s unshakeable belief that God will save Joel, Ryan’s envy that he cannot be so sure. I have no qualms admitting that I found the Christian overtures difficult. I am not a religious person. I do not believe in God. But I do believe that faith and hope can help people in their darkest times. At least I do now.”

The story of the real Joel Green is not without its miracles. Doctors expected Joel to live just four months after he was given his terminal diagnosis. He survived for four years. (He died in 2014.) And while That Dragon, Cancer was an emotional experience for me, I only broke down during the credits, when pictures of Joel and the whole Green family began to run. I felt like I had gotten to know them all during the course of the game—despite their featureless faces. To see them … it impacted me in a way I wasn’t expecting.

In the scene in the hospital room, nothing works. Joel’s cries grow ever extreme. The in-game Ryan, in despair, sinks into a too-small chair. “I am empty,” he admits—a desperate prayer to an unseen God. “You are … I don’t know all that you are. You are there. I want you here. I want you here. I want you to calm my son, and you’ve brought us this far … He’s still here. Not dead. Not there with you. I want him here with me. Please.”

And in that quiet, desperate moment, Joel becomes quiet. There is peace.