To mark the sad anniversary of Robin Williams’ death, Esther O’Reilly posted last week the first three of her top five performances by the much-missed actor and comedian. Now she’s back with her top two selections. Both surprised me a little—and they might surprise you, too, as she alludes to in her introduction. But it makes me want to watch both again.

***

To reward all you patient readers for bearing with my ramblings, I’ve put in a link at the end of this post to a small video tribute that I put together last year. It came together in what I can only describe as a white heat of inspiration after a few weeks of immersing myself in Robin’s work, incorporating material from several selections on this list. It seems to have struck a chord with viewers on YouTube, and I hope that it will move you as well. You can read a making-of piece that I wrote about it at my own site here.

Now, for the top two choices. After last week’s lineup of favorites, folks may wonder if there’s anywhere left for me to go. Of course, I think there is, though my choices may surprise you. The top two films both reveal something I appreciate about Williams as an actor: He understood how to play his part in the whole. When a movie really “belonged” to another actor, he could give a performance that was memorable without taking anything away from the lead. While people love those flashy roles where he may as well have been playing himself, like Mrs. Doubtfire or Good Morning Vietnam, Williams produced some of his best work when he was forced to disappear completely into a character. That’s the mark of a true actor.

2. Insomnia

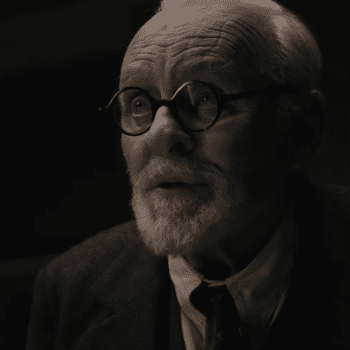

This underrated Christopher Nolan film is the biggest upset, but I’m ranking it so high for a simple reason: It’s an incredible piece of filmmaking on every level. Williams supports Al Pacino in the lead, but he matches the legend stride for stride in their scenes together. No easy feat, and no easy role. This is a detective thriller, so I can’t give away too much of the plot, but since the film itself gives away the identity of its killer pretty quickly, I can reveal that he’s none other than our beloved Robin. It’s shocking, but it’s brilliant. That open face, those twinkly blue eyes… who would ever suspect? As your doting granny might say, “He’s such a nice, nice man.”

Pacino plays weathered detective Will Dormer, investigating a homicide in an unusual locale: a part of Alaska where the sun never goes down in the summer. One sleepless night, he gets a phone call. A friendly voice on the other end says, “Can’t sleep, Will? Me neither.” Dormer threatens to hang up unless the speaker identifies himself. “Oh no you won’t,” the voice replies affably. “You need the company.” Of course, it’s the voice of Robin Williams, a voice with which Dormer will become all too familiar over a week of sleepless nights. Mornings find him staring at the alarm clock he always sets, just in case, waiting for it to start blaring so he can turn it off.

Dormer is a good cop and a good detective. But something terrible has happened in the course of the investigation, a terrible accident. And nobody knows what really happened, except him. Well, almost nobody. The guy on the other end of the phone knows. There’s the rub.

What follows is a fascinating study of corruption, conscience, and integrity. The story takes its time to unfold, but not a minute is wasted. In the style of Nolan’s early work, you come to understand how each piece plays an integral role in the puzzle. The characters completely draw you in, with hardly a false note in their dialogue. Important plot points are revealed in an understated way, trusting the viewer is smart enough to pick up on them.

Nolan’s work is sometimes known for its cynicism, but what I really like about this one is that integrity wins in the end, though it’s not an easy victory. It’s actually a remake of a Norwegian film by the same name, but it makes some significant changes, all for the better. It removes gratuitous sexual content from the original, makes the main character more sympathetic, and gives the whole thing a far more satisfying ending. I don’t mean that the ending is cheap, or trivially happy. Far from it. But it’s not cynical either. It’s the right ending.

As Thomas More says in A Man For All Seasons, “When a man takes an oath, he’s holding his own self in his own hands like water, and if he opens his fingers then, he needn’t hope to find himself again.” This is the truth that Dormer must grapple with. Few contemporary movies have offered such a compelling examination of it.

1. Awakenings

Here we are at number one, and I promise you that I didn’t just pick these films for my top two so I could juxtapose the titles Insomnia and Awakenings. (Kinda cool how that happened though.)

Some of Robin’s movies are appropriate for different tastes and types of movie-goers. But I can say confidently that this one is a must-see for everybody. It is based on the real life work of Oliver Sacks, a British-born neurologist who wrote about his experiences practicing medicine in the United States. His book of the same title describes his studies of encephalitis lethargica, a viral post-WWI epidemic that killed 5 million and left countless others catatonic from brain damage. Some patients were children when they first became ill. When Sacks found them as middle-aged men and women 40 years later, all other doctors had given up on them long ago. But Sacks was just beginning.

Williams plays Doctor Sayer, who is based on Sacks but has some fictional qualities. We first meet him as he arrives at a chronic hospital in the Bronx and quickly realizes there’s been a misunderstanding about the position he’s applying for. They need a staff neurologist, but he was looking for a job in a neurology lab. But despite his lack of clinical experience with human patients, the hospital is so understaffed that they hire him anyway. Quiet and terminally shy, he is clearly overwhelmed as an aide leads him through the ward of staring, drooling, twitching, ticking people. “We call this place the garden,” says the aide cheerfully. “ ‘Cuz all we do is feed and water ‘em.”

One day, they bring in a new patient, a woman called Lucy. She sits staring blankly in her wheelchair, not moving or speaking. Sayer gently removes her glasses, polishes them, then accidentally replaces them in a slightly off-set way. He turns his back to enter her data, but when he looks back at her, she is slumped over with the glasses clutched in her hand, as if she had bent to catch them from falling. Instead of putting them back on her face right away, he tries an experiment. He holds them carefully in front of her and deliberately drops them. Like lightning, her hand comes up, and they are caught in mid-air.

Sayer tries another object, a baseball. The same thing happens. But nobody is interested. Not even the old doctor who was there when this generation first “fell asleep” can offer encouragement. He plays a silent slideshow of his work for Sayer, pausing on one image of a man with his hand raised limply and his mouth hanging open, like the figure in Munch’s The Scream. Sayer draws closer and wonders aloud, “What’s it like to be them? What are they thinking?” “They’re not,” the doctor replies curtly.

The rest of this film stands as a quiet devastation of those words. And it is all too timely in this day and age, where people like Terry Schiavo can still be deemed legally unworthy of life. Moreover, the arrogance of the culture of death is not merely moral, but scientific. When Experts make airy pronouncements about brain function, they presume to understand physical mysteries science has only begun to unlock. The doctor’s words melt into insignificance as Sayer conducts further tests, working with his staffers to trigger more responses. He can play a game of catch in a circle, and nobody misses a beat. Flick on the jazz station, and a woman will begin eating her porridge, while another man won’t eat without his rock and roll. And if you give Lucy’s eyes an unbroken pattern across the floor, she will walk across it of her own accord. Why? To look out the window, of course.

These experiments ultimately lead Sayer, as they led Sacks in real life, to put the patients on the drug L-Dopa. You may recognize the drug as a Parkinson’s treatment, which it already was in Sacks’s day as well. The results of these drug tests with the victims of “sleeping sickness” were equal parts extraordinary, beautiful and heartbreaking.

Sayer’s first test patient is a man named Leonard, who becomes the main character and is beautifully played here by Robert De Niro. Like Pacino, De Niro is another legend with whom Williams holds his own while selflessly standing just out of the spotlight. Leonard is brought fully to life by the drug, and eventually, his fellow patients are as well. As we embark on this journey with them, we sense their mingled pain and delight. It is the pain and delight of a generation discovering the world afresh, only to realize that it is not their home.

I cannot promise you a happy ending to this true story. In fact, I must tell you to prepare yourself for moments of almost unbearable sadness. But it will change you. It will change you in that way that all great stories change you: by making you see.

In the clip I’ve embedded above, Leonard calls Sayer excitedly in the middle of the night, saying he needs to talk to him about something important. Sayer wearily drags himself to the hospital, and Leonard sits him down. “We’ve got to tell everybody,” he says. “We’ve got to remind them. We’ve got to remind them how good it is.” “How good what is, Leonard?” Leonard explains that it is the gift of life. “People have forgotten what life is all about… They need to be reminded of what they have, and what they can lose.”

This was one of the first movies I sought out and watched after Williams’s death, and it was this scene that haunted me, above all the others. For in the end, it was Williams who perhaps forgot what life was all about. It was Williams who needed to be reminded of what he had, and what he could lose.

“How good what is?” he asks. “How good what is?” It is life, and life.

Say it louder. Say it again. Say it to the last syllable of recorded time. For the shadows are lengthening, and the world is listening.