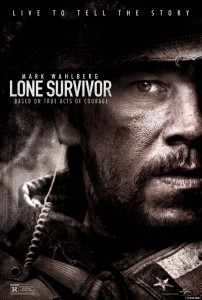

Review of Lone Survivor, Directed by Peter Berg

Eleven years ago, when I was in the Army, some fellow troops and I went to see the Vietnam war movie We Were Soldiers (2002). We were a crowd of young guys who didn’t know anything, accompanied by one old master sergeant who was a Vietnam War veteran. The younger soldiers loved the movie and, afterwards, were palling around like normal. The old master sergeant was walking alone, quiet. I asked him what he thought of the movie. “There are some things you don’t need to see again,” he said.

His words came back to me after watching Lone Survivor, Hollywood’s first major film set in the Afghan war.

I.

There are two kinds of war movies. There are those in which war is necessary and just, no matter how harrowing and violent. These tend to be set in World War II, the war that audiences have the easiest time sympathizing with. They are stories of courage and loyalty and sacrifice among a band of brothers pulling together for the greater good. Think of Sands of Iwo Jima (1949), The Big Red One (1980), and Saving Private Ryan (1998).

Then there are movies in which war is futile, stupid, dehumanizing, brutal, and sometimes evil. These movies tend to be set in Vietnam. Think The Deer Hunter (1978), Platoon (1986), and Full Metal Jacket (1987). They are stories of alienation, cruelty, isolation, and loss by soldiers sent to die for nothing. There are some exceptions (The Green Berets, 1968), but the templates generally hold.

Lone Survivor is the first big-budget feature film set in the Afghan war. It is the true story of four Navy SEALs hopelessly trapped and surrounded in the mountains of Afghanistan, and of their lost-cause firefight against an overwhelming enemy. I expected the movie—indeed, any movie set in Afghanistan—to follow the Vietnam template. Most of the country has concluded that these wars were not worth fighting, that we didn’t win, and that therefore the only stories that can emerge from them are stories of loss and despair.

I was wrong. Lone Survivor is closer to being The Hurt Locker of the Afghan war. The Hurt Locker, winner of the 2009 Academy Award for Best Picture, is the story of a single soldier’s experience in Iraq that avoids commenting on the war itself. Similarly, Lone Survivor is technically brilliant, intense, violent, and wrenching, and almost neutral about the war. I say almost because in the end, the film astonished me: it presents both faces of war and answers the question—is it a good war or a bad war?—with an Afghan answer. This is one of the best and most profound American war movies of the last thirty years.

II.

I’ve written before about my own experience with Afghanistan. I served there in 2002 and spent the next decade working on the war as a civilian in various positions in and around Washington, D.C. As with Zero Dark Thirty last year, I felt something personal at stake in the film and found it deeply unsettling to watch.

On one level, the movie will be hard for anyone to watch, whether veteran or not, because it is a brutally violent film. Following in the footsteps of Saving Private Ryan, Black Hawk Down, and We Were Soldiers, the film shows the horrors of combat in unstinting detail. Once the shooting begins—maybe a full hour into the movie—it is an unremitting succession of men being shot, blown up, thrown against rock, shredded by shrapnel, stabbed, or plummeting to their death. Interestingly, the hardest thing to watch didn’t involve guns or bombs at all: a scene of men tumbling down a hillside elicited audible gasps and groans in my theater.

Some of what the SEALs endure borders on implausible, but the filmmakers open the movie with a documentary montage of Navy SEAL training that establishes how impossibly tough these guys are. The film manages the delicate balance of showing incredible action while keeping it grounded in horrible realism (heightened by superb sound editing—note the report of different caliber firearms echoing off the surrounding hillsides). Saving Private Ryan had long sequences of story in between major set-piece battle scenes: Lone Survivor is essentially one long continuous battle for a solid hour or more. It is on the borderline of sadism, saved only by its fidelity to history.

Despite the violence, the filmmakers (led by director Peter Berg) are at pains to deny viewers any sense of thrill for most of the film. The camera quickly cuts away from the Taliban when they are cut down and avoids showing their faces in death. The lens moves so quickly it is hard to make sense of the action—an intentional technique to make the viewer as confused and addled as the soldiers. The filmmaker’s one nod to the inspiring-war-movie-trope is in giving the doomed SEALs clean, noble deaths. Lt. Mike Murphy won the Medal of Honor for his heroism in this battle—the first such award since Vietnam—and the movie gives us a brief moment, too brief, of old school war-hero-worship.

[Spoilers ahead]

III.

The movie teeters on Vietnam clichés, forgivable because they are true. Bureaucratic blunders, officers’ arrogance, and technical breakdowns contribute to the disaster. The SEALs are trapped because their radios and phones don’t work. The quick reaction force can’t take off on time because their escort has been called away, and when it finally flies to the rescue it only brings more mayhem. A senior officer doesn’t care about the situation and barks, “Why are you telling me this?” These elements would be at home in any Vietnam war movie, and they hurt because they’re accurate. A fellow veteran once told me that wars are won by the side that is slightly less stupid. Sometime I wonder how we win wars at all.

But the film holds this in balance with two elements so incredible that they would be contrived and cheesy if they were fiction. The whole crisis is triggered when the SEALs are discovered by Afghan goatherders. The SEALs tie them up and debate whether or not to execute them on the spot—a debate marked by neither idealism nor barbarity, but simple pragmatic calculation. They decide to do the right thing and let the Afghans go—the sort of nobility reminiscent of the old Good War template. “Good things happen to good people,” one of them says, which is bad theology but an accurate reflection of how people think.

After the battle, the titular lone survivor is rescued by Afghan villagers (good karma coming back to reward him), who are then attacked by the Taliban and rally to defend themselves. The SEAL, wounded and barely living, is a peripheral character in the final battle between Afghans and Afghans. Explanatory text closes the movie, informing us that the Afghans protected their American guest out of their sense of tribal hospitality—more Good War echoes—and that their war against the Taliban continues.

With these elements, Lone Survivor presents both faces of war. It is stupid, noble, cruel, necessary, barbaric, and just at the same time. More: Lone Survivor, almost alone among American war movies, manages to be about more than just some American soldiers and their enemies. This movie ends up becoming a story about the Afghans in whose country the war is taking place. In that sense, the movie, which starts out as a small-scale story of four SEALs with no evident commentary on the war itself, ends up sidelining its heroes and focusing front and center on the real heart of the war: it is the Afghans’ war.

I cannot imagine American audiences showing up to watch a historical drama about a third-world civil war. The filmmakers know it, so they only give us the briefest of denouements that suggests what such a movie would be like (the movie ends too abruptly, one of its few major flaws). It is still vastly more than I expected, and it effectively doubles down the emotional toll of the film. Few can doubt that the villagers’ resistance to the Taliban’s brutal thuggery is a good war, whether we are a part of it or not. I was dumbstruck that the first movie about the Afghan war got it exactly right.

IV.

I wish I could end there. But there is one final observation I have to make about the film. I remember my old master sergeant’s words again: “There are some things you don’t need to see again.” I thought he meant he didn’t want to see the firefights, the death, or the bloodshed. Now I think there’s something else. Watching a movie about my war struck a raw nerve.

When I watch a World War II movie, the Nazis don’t frighten me. I’ve never met a Nazi. I know they were defeated, and they are ancient history. Watching the Taliban on screen, watching them assault the Afghan villagers, was deeply disturbing. I felt personal hatred: a righteous, blinding, murderous rage. When our Apache helicopters came to the rescue and slaughtered them from the air, I was drunk with delirium. I think when my master sergeant said there were things he didn’t want to see again, he wasn’t talking about images of violence. He was talking about what we see inside ourselves in wartime.