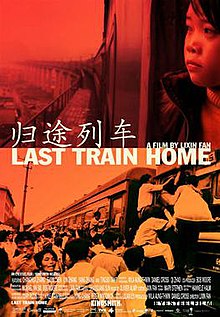

Review of Last Train Home, Directed by Lixin Fan

The documentary Last Train Home tells the heart-wrenching story of a family caught in the turbulence of an industrializing China. Every Spring, for Chinese New Year, 130 million migrant workers trek back to their rural homes to rejoin their families, only to return again to their urban employment. The film was released in 2009 and now, four years later, the story is still relevant.

Zhang Changhua (father) and Chen Suqin (mother) have a teenage daughter (Qin) and a young son (Yang). The family is based in Sichuan province, but the father and mother left to Guangzhou to make money in a clothes factory 16 years ago, where they work all day on sewing machines. They’re able to visit their children once a year during the Spring Festival holiday and make occasional phone calls. Their oldest child, Qin, is now a teenager.

Naturally, family relations are strained. Early in the film, Suqin, the mother, admits that when they’re home with their children, they don’t really know what to talk about. Qin, the daughter, is resentful of her parents for leaving them and wishes that they wouldn’t visit at all. The children were raised by their elderly grandmother. They go to school and help on the farm. When the parents do return, their conversations revolve around exhortations to work hard in school, the importance of education, the need to excel in their grades.

The conflict in Last Train Home centers on Qin’s relationship with her parents. Qin decides to drop out of school and pursue employment. She ends up in a similar job as her parents, working in a garment factory and running sewing machines. The parents beg her to reconsider, but Qin prefers to make money rather than invest in her education. The three of them return back home together for the holiday and the water rises to a boil until finally Qin speaks her mind about her feelings toward her parents, which leads to a physical fight between Qin and her father. Qin leaves and returns to the city, but starts working at a bar as a waitress.

Last Train Home received piles of awards and for good reason. We truly get up close and personal with this family and a the same time we get a taste for the harsh realities that accompany industrialization. The most moving scenes, only second to watching these parents explain their hopes and dreams for their children, are watching the crowds waiting to get on trains. The sea of people wait up to a week outside the train station. Tickets get sold out, trains get delayed, and chaos is everywhere. Police and what look like military personnel try their best to keep the mobs calm.

When I watched this human ocean surge and try to overtop crowd barriers, I found myself (literally) shaking my head in disbelief. Just watching it made me frustrated at the inefficiencies. Imagine what the people must feel. Desperate people were crying, exhausted women collapsed when offered a chair. But there was no real enemy but the birth pangs of trying to grow the economy of the largest population on earth.

Changhua, the father, stood out most to me. While the mother was the chatterbox, the father was often silent, but was clearly not a passive figure in the family. In the midst of waiting for several days for the trains to arrive, the Changhua didn’t crack. Maybe people get used to this after many annual pilgrimages home, but the camera captured many moments of outrage by other travelers. When the train arrived and the pushing and pulling began, Changhua made sure his wife and daughter made it onto the train, and spoke gently to make sure they boarded in a safe manner. For me, personally, the father was the hero of Last Train Home (as much as an issue documentary can have a hero).

The moral issues in the film are ambiguous at best. The parents left their children to make money to send home. Can money replace good parenting? Of course not. But in difficult situations such as this family faced, there’s no good answer. Instead of making judgment calls, the right posture of the viewer should be to acknowledge the difficulties in urbanizing China, weep with those who weep, and celebrate the steadfastness of these parents to provide for their children.

In mainland China, it’s common to hear folks bemoan the moral lacuna in modern Chinese society. But we should remember the blessings of common grace that allow great displays of selfless love. We were reminded of this truth just this last week. A 7.0 earthquake struck Sichuan on April 20, the very same province that our documentary’s family is from. And much like in the Boston bombings, many brave people ran toward danger to help the needy. As Christians, we should pray that the Lord come quickly to set things right and in the meantime that the Lord restrain evil and bless human flourishing.