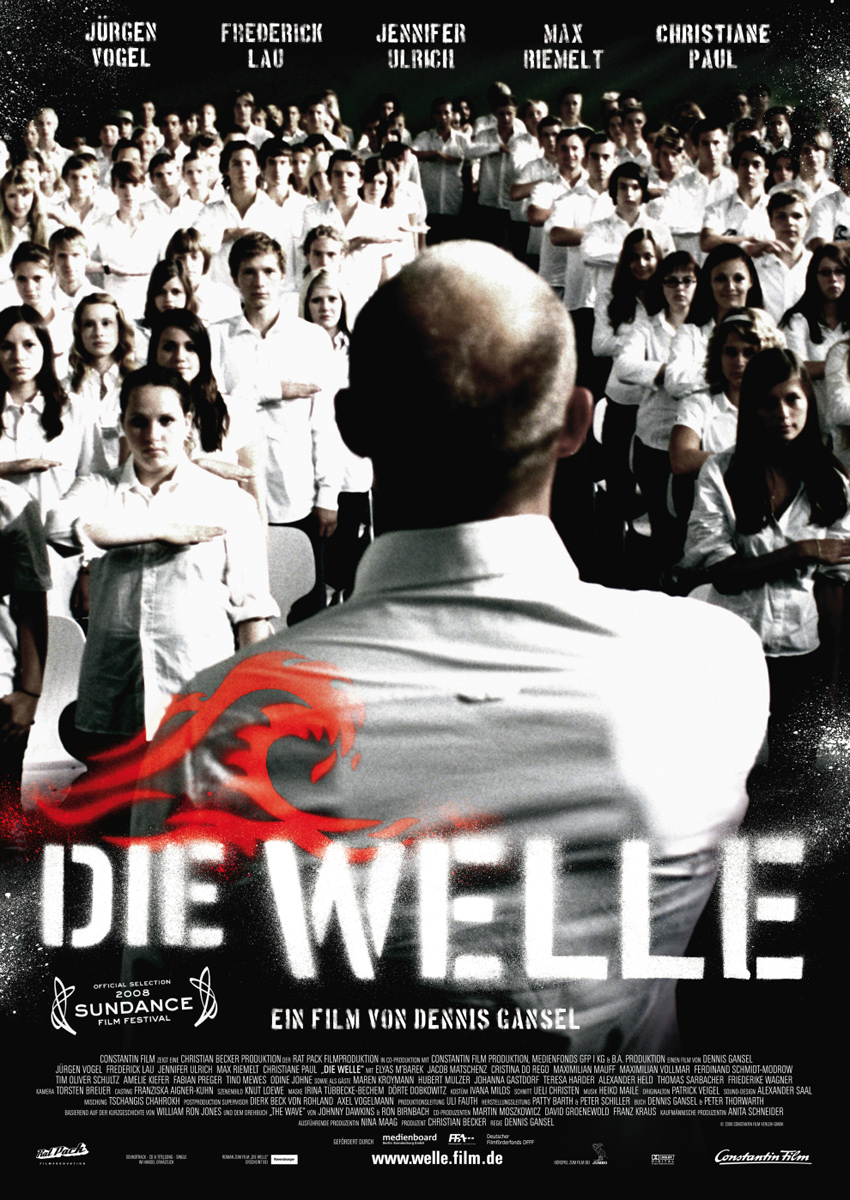

Review of Die Welle (The Wave), Directed by Dennis Gansel

By KENDRICK KUO

Is a resurgence of fascism possible? Die Welle answers yes.

This German film is based on a 1967 social experiment in a Californian high school that sought to recreate a fascist society in a world history class. “Die Welle” means “The Wave” and is the name of the student group formed in the experiment. (In the actual experiment, the group was named “The Third Wave”.) In Die Welle, the experiment takes place in a German high school “project week” class titled Autocracy. Rainer Wenger, the teacher, decides to run a weeklong experiment to emulate what it would be like to live under a fascist regime similar to the Nazis. He is addressed as “Herr Wenger,” students must stand up before they speak, march together in rhythm, don a uniform of white shirt and jeans, create their own symbol, and have a special salute.

As I’m not entirely familiar with the actual events, I will not try to parse out what was real and what was not—other than to say my cursory look into the online resources revealed that a number of elements were accurate. The main differences were that firearms were not involved and that the ending in the movie was purely for cinematic punch—the experiment ended peacefully and the teacher was not arrested.

The story centers around Herr Wenger, Tim (an insecure, mentally unstable student), Marco, and Karo (Marco’s girlfriend). Karo is quickly ostracized from the Die Welle because she refused to wear the uniform and develops into the most outspoken opponent of Die Welle. In the process, she is estranged from Marco—a ready devotee of the group. The first signs of group unity begin when two members of Die Welle defend Tim, a clearly unpopular kid in school, against two bullies. Ironically, one of Tim’s defenders is himself a bully who begins to reform through Die Welle and befriends Tim. Soon Die Welle goes on a PR campaign, sticking their logo throughout the city, throws a beach party that’s limited to Die Welle members and friends, and only allows members to use the skateboarding half-pipe.

The film reaches its climax at the very end, when Wenger is confronted with the choice of whether or not to “relinquish power” and disband Die Welle. He admittedly enjoys the way his students now listen to his every word, but his wife and Marco insist that things are getting out of hand. Wenger holds a Saturday rally in the school auditorium to which hundreds of students attend, all wearing the white shirt, blue jeans uniform. During an inspiring speech of how Die Welle will wash over Germany and reform the country, Marco stands up and decries Wenger’s megalomania before the other students. Wenger orders Marco to be brought onto the stage, and the rally falls into hysteria, Die Welle members outraged by Marco’s impudence. But then Wenger turns the tables and rhetorically asks his captive audience what they expect him to do. Kill Marco?

With a sigh of relief, the tension is broken as Wenger explains the moral of the story: dictatorship is still possible in even a democratic society and must be guarded against. Unexpectedly, Tim pulls out a gun and threatens to kill Wenger for taking everything away from him. Die Welle had become his family and the anchor of his sense of belonging. Instead of killing Wenger, he turns the gun on himself. This lends weight to Wenger’s warning—within a week, Tim the insecure outcast had become part of a group and devoted to the cause to the point of violence.

After watching Die Welle, I wasn’t shocked into a heightened vigilance against encroaching dictatorship in the United States. I was instead drawn to the powerful display of group identity and the innate desire to be part of a larger unit—a desire totalitarian regimes can easily twist to their own devices. This is why the hyper-individualism of Ayn Rand seems to me to be completely one-sided and incomplete. Perhaps there’s reason why group ideologies such as communism and fascism have succeeded in making the jump from theory to practice, while anarchism remains an untouchable ideal.

This is also why the church as a divinely-mandated institution has such a profound ability to address the human condition. It is in the church that true group identity, found in Christ, is exemplified in its most beautiful form. While totalitarian regimes abuse the human need for group identification, the church is the perfect fulfillment. Just as politics is sanctified in the church polity (authority rightly exercised coupled with submission rightly given), identity politics is resolved in union with Christ and with one another and crosses ethnic, class, and gender lines.

The church acts as an outpost of heaven, displaying the glory of God to the world. In this role, it must address the way groups function. The world’s conflicts are rooted in inter-group tensions, which is also sadly the case inside many churches where factions form based on various issues. To look different than the world requires a proper understanding of biblical ecclesial polity, which oftentimes means entering paradoxes. The church draws a line around its membership to distinguish itself from the world; yet at the same time must welcome new members who leave the kingdom of darkness. Members must submit to their elders; yet at the same time abuse of authority must be kept in check. This is in stark contrast to the group identity depicted in Die Welle, with its burgeoning personality cult, elitism, mindless submission, and abuse of authority.