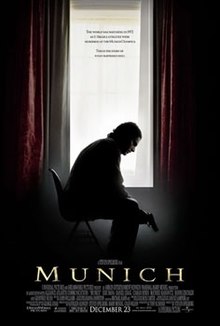

Review of Munich, Directed by Steven Spielberg

By PAUL D. MILLER

Munich (2005) is a sad movie. Unlike Spielberg’s other dramas—Shindler’s List (1993), Amistad (1997), or Saving Private Ryan (1998)—Munich ends without hope, full of questions, under a heart of sorrow. It asks “How do you balance the need to respond to terrorism with the knowledge that the response may provoke more terrorism?” In simpler form, “How do you balance justice with peace?” It is a heart-rending choice.

We see the heartache reflected in the four-man Israeli team at the heart of the drama. Avner, the Mossad agent assigned to track down and assassinate the Black September terrorists responsible for killing Israeli athletes at the 1972 Olympic Games, is not a trained assassin. His bomb maker is trained in defusing bombs, not constructing them. The two older members of his team are tough and crusty veterans of Israel’s wars, but we do not get the sense that they have fired a gun point blank at another human being. The assignment takes its toll, physically and spiritually, on each of them.

The film raises questions few other movies would touch. Avner’s bomb maker wonders if he isn’t losing his soul—losing his “righteousness”—in the act of vengeance. When was the last time you saw a movie character worry about his righteousness with a straight face?

It also includes an intelligent and sensitive portrayal of both Palestinians and Israelis. There is a Palestinian character who gives a moving speech about the plight of his people, but Avner’s mother gives an equally moving speech about the glory and the necessity of Israel.

[Spoilers ahead] The film is horribly tragic. Palestinian terrorists respond to the Israeli assassinations with more attacks, suggesting Israel’s tough counterterrorism approach is accomplishing nothing—even suggesting that Israel is simply provoking more terrorism. Yet can Israel simply stop its counterterrorism operations? The bomb maker and Avner, the two most affecting characters, have doubts about their mission, but they carry it out nonetheless. And through it all, images of the Israeli athletes’ murder play again and again, as if to say “Yes, there are difficulties and doubts and compromises—but these men are dead, murdered. Can we ignore that? Can we do nothing?”

By the end of the movie, most of Avner’s team is dead, and he might as well be. He can barely feel any emotion, even towards his wife. All he can think of are the 11 dead Israeli athletes, his furious attempt to achieve some sort of cosmic justice for them, and the moral compromises he had to make in his single-minded pursuit. He sacrificed his men and, he feels, his own soul; and now he wonders if he got anything in return.

In the final scene, Avner meets with his old handler one last time, with the 1970s Manhattan skyline in the background. Avner derisively spits “You know there is no peace at the end of this,” referring to the tit-for-tat escalation of violent attacks between Israel and Palestine. I wish the other character had responded, “Yes, but there is justice.” Instead, Avner then walks off in the shadow of the Twin Towers. The inclusion of the Twin Towers in the final shot of the movie is an unmistakable message from Spielberg. He unsubtly suggests we are caught in the same trap that ensnared Avner: we have morally compromised ourselves in our own struggle with terrorism and have only contributed to an endless cycle of violence.

If there is a flaw in the film, it is an oversimplified preference for peace over justice. Sometimes government does not have the option of peace. When enemies attack, the state has a responsibility to respond to defend itself and its people. That is the role God ordained government to play. The state “does not bear the sword in vain. For he is God’s servant, an avenger who carries out God’s wrath on the wrongdoer,” (Romans 13:4).

As the great 20th Century theologian Reinhold Niebuhr argued, earthly justice is established, if at all, only through “the assertion of power against power.” Justice “requires a measure of coercion,” which is itself “a necessary instrument of social cohesion.” We are to chose carefully the “ends and purposes for which coercion is used” rather than to hope for “the elimination of coercion and conflict.” Sometimes disrupting peace, and enduring conflict, is what is required of us. No doubt we should be careful in how we exercise that terrible responsibility, but we should not let our qualms paralyze us into inaction. Avner’s doubts are ultimately unjustified.

The United States has been at war with al-Qaida and its affiliates for more than a decade, and has killed many, many people. Munich suggests that we will not buy peace with such a war. That may be correct, at least in the short term. But could the United States have done otherwise? Could we have chosen not to respond to the attack of September 11, 2001? There will be peace again someday; but we pray that peace, when it returns, will a more just and lasting than before.

Paul D. Miller is a veteran of the war in Afghanistan. He previously served as Director for Afghanistan and Pakistan on the National Security Staff in the White House. The views here are his own.