Review of Die Hard, Directed by John McTiernan

By ALEXIS NEAL

Once upon a time, a man and a woman were married. Then one day, the woman left her husband. She moved far away and started a new life without him. She even abandoned his name.

Then this woman was captured by evil men who threatened to harm her. Despite everything, the man still loved his estranged wife, so he risked everything to save her from the evil men who had taken her freedom and planned to take her life. The man was wounded, bruised, and beaten, but he would not stop fighting for the woman he loved.

In the end, of course, the man was victorious. The bad guys were defeated, and the woman was saved. And when that woman saw her husband, bloodied and barely able to stand on his own two feet, she realized what he had endured for her sake, despite her faithlessness, and his sacrifice made her love him.

A compelling story, no? Romantic, to be sure. And more than a little reminiscent of the gospel story, wouldn’t you say? Christ sacrificing Himself for His bride, the church, even after lifetimes of sin and rebellion and idolatry. The bible is chock full of this stuff. All through the Old and New Testaments we see the recurring themes of sin, sacrifice, grace, and the love that grace produces, described in terms of marriage, infidelity, separation, and unmerited rescue.

But this particular version of the story doesn’t come from the Bible. It doesn’t even come from the romance shelf of the Christian Fiction section in your church library. The source is perhaps a surprising one: It’s the plot of Die Hard.

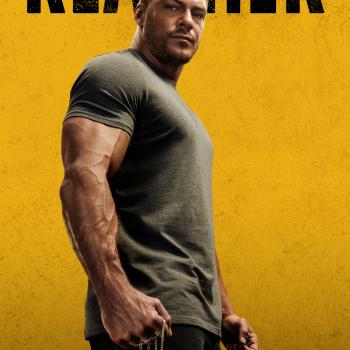

That’s right. Die Hard. Bruce Willis, Alan Rickman, Bonnie Bedelia, and a host of Hey! It’s That Guy-types from the 1980s. Hardly the place you’d expect to find the gospel. There’s swearing, for Pete’s sake. And violence. But then, the gospel is a bloody business, isn’t it? Sin isn’t pretty—it’s messy and filthy and disgusting and costly. And the cross isn’t clinical or antiseptic. The rescue of the church from the hostile forces of sin was not without consequences. Serious, bloody consequences.

Not that the violence in shoot-‘em-up movies like Die Hard is necessarily God-honoring violence, not is it treated with the seriousness that the gospel story deserves. And of course, it’s not a perfect picture—John McClane, though undoubtedly awesome in many, many ways, is not a perfect, blameless bridegroom wronged by a faithless bride. There appears to have been more than enough blame to go around in that particular marriage. And as much as I love the romantic side of the story, it is quite likely that McClane’s desire to kick tushy and take names (as well as his desire to help the many other hostages) may be a major motivating force behind his unassailably awesome defeat of the deliciously sneering Hans Gruber.

But all these shortcomings notwithstanding, there are undeniable similarities between McClane’s valiant rescue of his estranged love and our Savior’s dogged determination to save our sorry behinds, whatever the cost. For example, in Ezekiel 16, we see Israel compared to an abandoned infant adopted by a king. He cleans her up, gives her costly garments and jewels and what-have-you, and when she’s old enough, he makes her his bride (Ezekiel 16:1-14). Her response is to run around with countless other lovers (that is, the gods of the surrounding nations) (Ezekiel 16:15-34). There follows a graphic description of the prolonged and extremely unpleasant period during which the unfaithful bride experiences the consequences of and is punished for her actions (Ezekiel 16:35-59). But the Lord, in His mercy, does not leave it at that. Despite everything Israel has done, this is how He closes out the chapter:

Yet I will remember the covenant I made with you in the days of your youth, and I will establish an everlasting covenant with you. […] So I will establish my covenant with you, and you will know that I am the Lord. Then, when I make atonement for you for all you have done, you will remember and be ashamed . . .’” (Ezekiel 16:60, 62-63)

He makes atonement for the sins of His faithless bride. She sins. He suffers.

This theme plays out again and again in scripture. In Hosea, God instructs His prophet to marry a prostitute, and when she runs off with another man, God tells him to buy her back (Hosea 1:2-3, 3:1-2). Why? To show the people what God’s love is like: “Love her as the Lord loves the Israelites, though they turn to other gods . . .” (Hosea 3:1b). As we read through the book of Hosea, we see a heartbreaking picture of the Lord’s unfailing love for His people despite their repeated (and unrepentant) rebellion. We see the gospel in action. This pattern continues into the New Testament (where we learn that the invisible Church is the true Israel) and then on into the lives of Christians today. We sin. He pays the price. He effects a costly rescue despite our infidelity. And all we can do is love Him. He doesn’t save us because we love Him. He saves us because He loves us (Deuteronomy 7:7-8). Our contribution was rank and fetid sin. His response was grace. And it is only in the shadow of this grace that we truly learn to love our Savior.

Just like in Die Hard.

Laugh if you want, but it’s true. And really, we shouldn’t be surprised. People write stories and make movies that they think will sell—that others will want to read or see. And people, whether they realize it or not, long for the gospel. There is something in the story that resonates with us, even if we are resistant to the message on a conscious level. We’re wired for it. Maybe it’s Pascal’s God-shaped hole working its way into literature and film. Or maybe those media—and their creators—are just another facet of creation that “declares the glory of God,” even if they don’t intend to. Maybe the very rocks still cry out, even if the rocks are celluloid.